ED. NOTE: White and Blue Review’s ongoing series “What’s in a Number?” continues with a look at the best player to wear #23 for the Jays, Terrell Taylor. To read up on how we arrived at our choice, check out the introduction of the series. Or you can read about the players you might have missed by checking out the entire list.

Coming off a victory over Louisville in the 1999 NCAA Tournament, Dana Altman and his staff were tasked with replacing four seniors: starting center Doug Swenson, backup point guard Corie Brandon, backup forward Cliff Bates and all-time leading scorer in school history Rodney Buford. The resulting recruiting class was large both in terms of numbers and impact, and was the deepest class Dana Altman ever assembled — all six newcomers left their imprint on the program. Joe Dabbert, Mike Grimes and Michael Lindeman came in and all three were redshirted; Kyle Korver and Terrell Taylor came in and played huge minutes right away; and Livan Pyfrom transferred in and also played huge minutes.

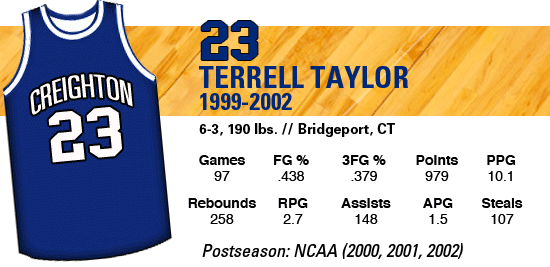

Taylor hailed from Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he averaged 25.1 points, seven rebounds, five assists and five steals a game during a senior season in which he also shot 57% from the field and 44% behind the three-point line. His high school team mascot was the Hilltoppers (the original nickname of Creighton), and from the minute he set foot on the “other” Hilltop in Omaha, he was an exciting player. Possessing the rare combination of impressive leaping ability, lightning quickness and a soft shooting touch both from inside and outside the arc, Taylor was believed to be the player with the highest ceiling of the six newcomers. From his Air Jordan tattoo on his bicep to his insistence on wearing Jordan wristbands, socks and shoes, as well as choosing the #23, it was clear who he’d modeled his game after.

Averaging 7.4 points, 2.6 rebounds, 1.3 steals and 1.1 assists as a freshman, Taylor was named to the MVC All-Freshman team along with teammate Korver, Kent Williams and Jermaine Dearman of SIU, and P.J. Smith of Illinois State. His three-point percentage of 44.2% (34-77) was good for fourth in the MVC, and he was one of a remarkable five Jays among the top seven in the league in that category. His debut came in front of a robust “crowd” of 732 at Mississippi Valley State, a 70-62 Jays win that saw Taylor score 10 points on 4-5 shooting which included making 2-3 from behind the arc.

Two weeks later, he made 5-8 from the floor for 15 points on the road at Baylor, which started a string of three games where he shot 71.4% from the field (20-28), 9-12 from behind the arc, and averaged 18.7 points per game. That the third game in that stretch included a win over Nebraska only endeared him more to Jays fans. Against the Huskers, he had 21 points on 8-10 shooting and 3-3 from three-point range, adding in six rebounds, four steals and a block. It was just his sixth game in a Creighton uniform, and he was already becoming a fan favorite.

After that initial burst, Taylor struggled offensively, scoring in double figures just six more times, and topped out at 13 in a win over Northern Iowa on January 26. Once the postseason came, though, Taylor turned the switch back on.

In the MVC semifinal against Indiana State, the Jays rolled out to a 16-point lead early in the second half. Then Korver missed an easy layup, and the momentum shifted; a 17-0 Sycamore run ensued, giving them a one-point lead. Altman put Taylor into the game, and he scored eight points in just under three minutes as part of a decisive 12-3 run that gave the Jays the lead for good. At a time when Ben Walker and Ryan Sears were struggling, and Korver had made two critical mistakes, it was Taylor who put the team on his back and led them to victory by hitting key shot after key shot. They would win that night, as well as the next, and claim the MVC Tournament title.

The Jays then squared off with 24th ranked Auburn in the NCAA Tournament at the Metrodome in Minneapolis, and fell behind big early, 40-25. Again, it was Taylor in the middle of the comeback that saw the Jays erase a nine-point deficit with 12.6 seconds left. First Ryan Sears knocked down a three, and then after a turnover on the inbounds pass, Ben Walker dished it to Terrell Taylor, who buried another three with 3.8 seconds left. Auburn proceeded to somehow turn it over again on the inbounds pass, and as the Jays set up for an inbounds pass of their own, under their own basket, they needed one more three pointer to tie the game. The defense swarmed Taylor, who had just buried a three, but the pass went to Walker, who took a shot from the corner that was miraculously blocked by 7-footer Mamadou N’Diaye, coming out of nowhere to alter the shot. Even with the loss, it had been quite a freshman campaign for Taylor.

As a sophomore, Taylor started 29 of 32 games, ranking fourth on the team in scoring at 10.4 points per game. He also was third on the team with 41 steals (1.3 per game), third in assists with 63 (2.0 per game), and blocked 10 shots. The leading scorer in six games, he scored in double-figures 15 times — including seven of the team’s final ten games, as the Jays finished the season winning 11 straight games before their semifinal loss in the MVC tourney.

Once again when the lights were brightest, Taylor was at his best. In a key non-conference road game at Tulsa, a team that had not lost at home in two years, Taylor had 13 points on 6-11 shooting with five rebounds and four assists. And in a nationally-televised showdown at Southern Illinois on ESPN, Taylor led the way with 23 points on 8-11 shooting (5-7 from behind the arc), three assists, three steals and three rebounds in the Jays 77-63 win.

Other season highlights included a 20-point night against Indiana State in which he made 7-9 free throws; an 18-point night at Drake where he made 4-6 three-pointers; 15 points and six rebounds in a win over Georgia State; and 17 points each in three home wins over Evansville, Drake and Wyoming.

In the postseason, Taylor was again among the most dependable scorers. He had 15 points on 6-10 from the floor and 3-5 from behind the arc in a 63-41 quarterfinal win over SMS, and added 12 points, 6 rebounds, 2 steals, and 2 rebounds in the semifinal loss to Indiana State.

After two seasons, Taylor had become known for two things: a sometimes enigmatic personality that bothered the coaching staff, and a knack for having his biggest performances in the biggest games. While he could be a frustrating player — and he frequently was, especially in games against lesser opponents — there was little doubting his success in the clutch. But beginning with the offseason following his sophomore season, he found himself in Dana Altman’s doghouse for behavioral (and legal) problems.

And in his junior year, he started exactly zero games — this after starting 29 of 32 the year before. The reason for the benching was made clear to anyone willing to listen: Taylor had gotten away with poor practice habits and inconsistent effort for long enough. As Altman told the Omaha World-Herald after the season, “Terrell was an ‘A’ student doing ‘C’ work.” Trouble was, Taylor took the benching with a nonchalant attitude, instead of it lighting a fire under him to earn his starting spot back. So Altman began waiting longer and longer in games to put him in, sometimes until late in the first half. That didn’t seem to work either, at least, not until Taylor’s mother intervened to set him straight.

But ultimately, the benching only made their relationship more contentious. His defense suffered, as did his teamwork; while his offense increased, his assists, rebounds and steals all dropped, and in turn, so did his minutes. His shot attempts also skyrocketed, while his percentage of made baskets dropped — he attempted more than 10 shots a staggering 20 times, while making more than 50% of them in just two games. They weren’t three-pointers, either; these were jumpers, dunks and layups he was missing.

This isn’t to say he had a terrible year — he averaged a career-high 12.6 points per game, and scored in double digits 19 times. And despite his increasingly contentious relationship with Altman, he remained a shooter capable of carrying his team offensively on any given night. That made him plenty valuable, as he would show in a handful of games that year.

For example, in a tough-fought battle with Nebraska, he scored 18 points on 7-13 shooting and 4-6 from three-point range. Other games where he carried the offensive load included a 20 point effort on 7-14 shooting (4-7 from behind the arc) in a win over SMS; 19 points twice in three days in late February games against Bradley and Drake; and 16 points on 4-5 from three-point range in a win over Wichita State on February 17. And in a wild 95-93 overtime battle with Drake on February 13 in Des Moines, Taylor scored 28 points, including five in the extra period, on 10-14 shooting and 5-8 from long range.

When the postseason rolled around and the spotlights got brighter, Taylor once again flipped the clutch switch into the “on” position. In the MVC semifinals, he scored 19 points on 7-11 shooting as the Jays rolled over Illinois State, 90-63. And in the championship game, Taylor paced all scorers with 20 points as he made 7-15 shots and 5-6 free throws in the Jays 84-76 win.

But he’d saved his best performance for last.

In the NCAA Tournament against the Florida Gators, the player who’d modeled his game after Jordan got to play in Jordan’s House, the United Center in Chicago. He was perhaps a bit too hyped up early on, missing all six of his shots in a first half that saw the Jays fall behind 38-31. But his second half was one for the ages. Making 10 of 14 shots, and 8-10 from behind the arc, he scored 28 points after halftime — featuring three treys in the final 2:40 of regulation to rally the team from an eight-point deficit, and two more in the second overtime to give them the lead — and the game-winning three pointer with less than one second to play.

That performance was even more clutch when you consider Brody Deren had fouled out with 2:42 to play in regulation, and Korver had fouled out with a minute to play in the first overtime. How the game winning shot happened is the stuff of legend. Out of timeouts, and trailing 82-80, the Jays caught a break when Florida failed to get the ball inbounds, earning a five-second call. Suddenly having possession and a chance to win the game, but not having a timeout to draw up a play, they hurriedly called in a makeshift version of a play they’d designed and practiced prior to the MVC Tournament, intended to get a last-second shot for Korver. But as Altman explained to the media, “Usually, we bring Kyle off the top there, and Terrell is the guy that comes off the baseline. So we had to flip-flop that around.”

Taylor came off a double-screen near the top of the key, caught a pass from Tyler McKinney, and had a choice: drive around the corner and penetrate for a jump shot to tie the game, or fire over the outstretched arm of Florida guard Brett Nelson for a three-pointer to win it. He opted for the latter.

“I was kind of happy when Taylor pulled up because Nelson was all over him,” Florida coach Billy Donovan said later. “But he was in a zone today. Everything he threw up went in.”

It was another in the long line of games where Taylor had come up big when the lights were brightest. Sometimes frustrating in the regular season, once March rolled around, he was the team’s best clutch performer all three of his seasons.

After the season, he was voted MVC Sixth Man of the Year, was an honorable mention for the All-MVC Team, and was poised to come back as a senior on what would become the 29-5 juggernaut that spent much of the season ranked. But mere weeks after his tourney success, he decided to leave Creighton after a meeting with Altman where he laid down specific ground rules that Taylor would need to abide by. Unwilling to do so, he left.

Taylor’s departure coincided with that of another Connecticut guard, Ismael Caro. “Both young men felt it was in their best interest to look at other opportunities, and I agreed with them,” Altman told the Omaha World-Herald, noting the departures were mutual decisions. As for Taylor, he told the Connecticut Post that “It was my decision, if I wanted to deal with (Altman) or leave. We didn’t like each other, but our relationship was very professional and tolerable. I just thought my future would be better if I played somewhere else for my last year.”

His departure left the team to regroup without its second leading scorer, and the author of one of the most memorable shots in school history. For his career, Taylor finished 21 points shy of joining the 1,000 point club with 979, and ranks sixth all-time in school history in points scored in the NCAA Tournament with 56 — averaging 14.0 a game, well above his regular-season averages, further proof of his clutch play. And that’s what he’ll ultimately be remembered for by most fans. Not the enigmatic regular season player, but the guy who was clutch when it mattered most: in the postseason.

Terrell Taylor was, and remains, the greatest player to wear #23 at Creighton.

Also of note: Todd Eisner, who played from 1986-91 and scored 502 points with 218 rebounds in 98 career games. A 6’7″, 200 pound forward from Chilton, Wisconsin, Eisner was a sharpshooter and twice led the MVC in three-point shooting. Described by Tony Barone as “the glue — we can’t play without him,” Eisner was a key role player on both the 1989 and 1991 NCAA Tournament teams. He went on to coach at Bellevue University, where he twice reached the NAIA National Title Game, and returned to Creighton as an assistant in 2008 for two seasons on Dana Altman’s staff before leaving for another NAIA job at Benedictine.

Career Stats:

Season FG Pct. Pts Avg. Reb RPG Assists APG Steals

1999-00 .506 245 7.4 86 2.6 36 1.1 42

2000-01 .429 332 10.4 83 2.6 63 2.0 41

2001-02 .412 402 12.6 89 2.8 49 1.5 24

Totals .438 979 10.1 258 2.7 148 1.5 107