ED. NOTE: White and Blue Review’s ongoing series “What’s in a Number?” continues with a look at the best player to wear #32 for the Jays, Rodney Buford. To read up on how we arrived at our choice, check out the introduction of the series. Or you can read about the players you might have missed by checking out the entire list.

Rodney Buford is the leading scorer in school history, and was the first important recruit of the Altman Era; heck, given the abyss that Buford helped lead the team out of, it could be argued he was the most important one of the entire era, if you buy the line that what came after might not have been possible without the 1999 NCAA Tournament run. So its interesting, then, that as years go by, there seems to be a generational gap in the appreciation of Buford. Among fans my age and a bit younger — those who were at CU during the Buford years — he’s held almost in higher esteem even than Kyle Korver. Buford raised the bar for what CU hoops could be under Dana Altman. He was a human highlight reel whose career was a long line of electrifying moves, gravity-defying dunks and plays that made you question reality.

Yet there’s a significant portion of the CU fanbase that jumped on with Korver, and knows little about what happened before that. (Which was part of my aim with this series, incidentally, to help keep these names and stories alive). Doubt it? When he’s shown on the video board at the Qwest Center during the handful of games he attends each year, Buford gets little if any applause, because a good percentage of the crowd simply doesn’t recognize him. This is the leading scorer in school history, a guy who lived above the rim like few in a Jays uniform before or since and could electrify a crowd with the best of them, yet he’s entirely anonymous to a good percentage of the people who attend games. Its nuts.

He played in 118 games, which is ten fewer than Korver and Bob Harstad, six fewer than Chad Gallagher, and 17 fewer than Nate Funk. Yet he outscored all of them. There are only two players with more than 2,000 points in CU history, and only six to average more that 14 points a game in each of their four seasons. Buford is in both groups. But especially in his final two seasons, he did more than just score. He grew to become a pretty good — not great, but pretty good — defender. He has more steals than any player on the Top 10 scoring list, and you have to go all the way down to #16 on that list, Ryan Sears, to find a player with more than Buford’s 195. He has more assists than all but Korver among the Top 5 scorers, and while he’s well behind Harstad, Gallagher and Portman in rebounds, he has over 50 more than Korver. He also had a knack for making plays late in games, whether it was grabbing a key rebound, helping on a defensive stop, or making a big basket.

Ryan Sears, Ben Walker, Korver, Funk and Tolliver were all-time greats not only in the Altman Era, but in the history of CU hoops, but would they have come to Creighton if not for Rodney Buford helping lift them out of the abyss of the Rick Johnson Era before they arrived? Would Altman have lasted long enough to lead the program to the heights it achieved and recruit those players? If Buford had not signed on the final day of the spring signing period in the spring of 1995, if he had not put Creighton hoops back on the map by becoming a staple of SportsCenter’s top plays with his dunks, and if he had not convinced his former AAU teammate Ben Walker to join him, one wonders what would have become of the program. He’s that important. To understand how much, though, we first have to go back to the years before his arrival for some context.

Tony Barone Bails

Two weeks after losing to Seton Hall in the 1991 NCAA Tournament, Coach Tony Barone interviewed for — and then accepted — the head coaching gig at Texas A&M. Barone had went 102-82 in six seasons with two NCAA Tournaments, one NIT, two regular season MVC championships, two MVC tournament championships, and recruited two of the greatest Jays ever in Harstad and Gallagher. In fact, by going 20-11, 21-12 and 24-8 to close out his stay in Omaha, Barone was the only Creighton coach at the time to post three straight 20-win seasons. His departure, which coincided with the graduation of the Dynamic Duo, was a devastating blow to the program.

On March 21 of 1991, the World-Herald’s Michael Kelly wondered if lukewarm fan support played a role.

If Tony Barone leaves after a successful six-year run as Creighton University basketball coach, which would surprise no one, marginal crowd support might be one reason. “You have to be at a place where the community embraces the team,” he said this week, while remaining noncommittal on his plans. . . Home attendance this season averaged 6,337, up 2.4 percent from last season’s 6,190 – which was 20.9 percent higher than the 5,117 the previous season, when the Jays, as they did this year, won the Missouri Valley Conference regular-season and tournament titles and played in the NCAA tournament. Creighton never had a home sellout during the Bob Harstad-Chad Gallagher era that ended with this year’s school-record 24-victory season.

Whatever the reason, on April 9 of that year, Barone was named as the coach at Texas A&M. Harstad publicly called for assistant Dick Fick to be named as his successor, as did several other players, with Harstad telling the World-Herald, “This isn’t a sales promotion, but I think if Coach Fick takes over, in my eyes, the program will stay where it is and it will even get better.” Fick, for his part, wanted the job, saying “We’ve got great kids here, I’ve recruited most of them, and I would love to coach them.”

Nonetheless, athletic director Dick Myers named another Barone assistant, Rick Johnson, as the new head coach six days after Barone’s departure. Fans, ex-players and media jumped at Myers, openly ripping his pick and expressing their disappointment. Myers responded at the press conference that “Dick was the more visible of the two, particularly the last two years because of all the recruiting. So I’m sure there are going to be some people surprised. But again we did not want to be swayed by the sentiment and maybe the pre-appointment of the obvious candidate. We wanted to make sure both candidates had every opportunity.”

The World-Herald called it “a blunder”, using those exact words, and added:

(Fick) came to CU shortly after Barone was hired, and was an architect of the rebuilding plan. At a summer camp, he spotted a lightly regarded high school player named Bob Harstad, who became the leading scorer in Creighton history – and last week endorsed Fick. Fick was always on the bench next to Barone. Two years ago, with Barone ready to go to Marquette before that deal fell through, the way was paved for Fick to become Creighton head coach. But since then, there’s a new athletic director, Dick Myers. And a new vice president, George Grieb…

Three years later, Johnson had compiled a 24-59 record and a .289 winning percentage, winning fewer games both in the conference and overall in successive each year — from 9-19 (7-11 MVC) to 8-18 (6-12 MVC) to 7-22 (3-15 MVC). Clearly, not only had the program slipped considerably, it was going downhill. They were the worst program in the league, playing in a crumbling arena with dwindling fan support and rumors about the school’s commitment to Division 1 athletics. Yet Creighton had never — yes, never — fired a basketball coach.

How bad were things? They lost 14 games by 13 points or more in 1993-94, and had just three crowds larger than 3,000. One of those was for Nebraska, when they drew 8,383 — a full 1,000 below capacity. Take away that crowd, and their average attendance was 2,352 and an even more ghastly 2,289 for MVC games. Their record was sliding, the players who remained from the Barone/Fick era were now gone, and it was unclear what Johnson’s plan was for rebuilding the team.

In March of 1994, Tom Shatel laid the blame for the state of CU hoops not at the feet of Johnson, but at former AD Myers, calling the hire “a classic case of mismanagement.” He added the factual statement that Myers soon departed CU, not sticking around to see how his choice would fare.

Shatel then laid bare the state of the program, and its future:

Where Creighton goes next is a good question. The answer will decide the future of CU athletics. Basketball pays the bills. Now the ball and the tab are squarely in the court of Creighton’s president, the Rev. Michael Morrison. His decision: Should he gamble that Johnson will start winning? If not, he could risk losing many more fans – and booster money. Could Creighton recover from another 7-21 year?

There are some Jaybackers who fear Morrison may let the program slip all the way to Division II and cause the NCAA to move the College World Series away from Omaha. I don’t buy that. The NCAA doesn’t care if Creighton wins eight or 18 basketball games.

But there are plenty of Bluejays who still do. They yearn for the glory days. It’s time to bring them back. Before it’s too late.

Ominous, right? A few days later, facing increasing heat, Johnson resigned. Creighton has still never fired a coach in basketball.

Enter Dana Altman

Altman came from Kansas State, where he compiled a four-year record of 68-54 at Kansas State, including a 20-14 record his last season and a trip to the Final Four of the NIT. A quality coach with a proven record who nonetheless was probably one year away from being fired from his Big Eight job, he instead left of his own accord and came to Creighton (sound familiar?). His first year, he had to work with what Johnson had left him, which wasn’t much, and the Jays had only marginally better results, finishing 7-19 and 4-14 in the MVC. They were still mired in last place. They shot an vomit-inducing 55% from the free throw line. They lost 11 of their final 12 games.

But in the offseason, the Jays lost three players to graduation and four more who were either asked to leave or left of their own accord, leaving Altman and staff essentially a clean slate to rebuild from. They signed JuCo players Chuckie Johnson, Carteze Loudermilk and Edward St. Fleur to give them immediate help, and freshmen Rodney Buford, Kevin Mungin, Chris Chestnut and Lamont Scott to build for the future.

The last of that group of seven players to sign, Buford was seen as the key building block. He averaged 19.0 points and 7.0 rebounds during his senior season at Milwaukee’s Vincent High School, leading them to an 18-4 record while earning second-team All-City Conference honors. At the time of his signing, his coach Tom Diener commented, “Rodney has a tremendous amount of potential. I don’t have any problem in saying that I think he has the most potential of any high school player coming out of Wisconsin this year.”

Diener told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel that “Rodney attracted a lot of attention, but he didn’t get his test scores until late. A lot of schools took a wait-and-see approach with Rodney, but by the time he cleared, they had already signed other kids. A lot of schools weren’t willing to wait for him. Creighton did. They stayed with him all the way.”

Greg Grensing had recruited Buford, and as the staff watched him in summer tourneys prior to his senior season, Altman wavered. Grensing spent over a year keeping Buford on the staff’s radar, while staying in contact with Buford. That tenacity finally won the head coach over, and the Jays saved a scholarship back just in case his test scores came back high enough for admission. When they did late in the signing period, the Jays got a highly-regarded player who came in ready to prove his doubters wrong.

A Stellar Freshman Campaign

Picked for last place, the Jays instead won twice as many games as they had the year before, going 14-15 (9-9 in the MVC) and finishing tied for fifth place. In their first exhibition game, which drew a paid attendance of 3,335 but was estimated by Steve Pivovar of the World-Herald to actually be somewhere south of 1,000, Buford scored 24 points in a 77-68 win over Poznan of Poland. He made 11 of 15 shots, including the first thunderous fast-break dunk of a career that would include too many to count.

Dana Altman showered him with praise after the game — at least, as much as he ever did with any player, in his typically understated manner. “It was nice to see Rodney get off to a good start. I’m sure he’s feeling awfully good about his offensive production, and he should. But he also has to realize that he’s got a lot to learn.”

For his part, Buford understood that, and told the World-Herald afterward that he was surprised to have played 21 minutes, saying that “I thought my defense would have to get better before I would play that much.”

In their second exhibition, played before 1,700 fans at the Civic, Buford again threw down a thunderous fast break dunk. While hardly anything to write home about for most programs, the dunk — combined with a similar one from fellow freshman Kevin Mungin — showcased a level of athleticism that simply did not exist in the Rick Johnson era, nor in Altman’s first season. He gushed about it in the media room after the game:

“We went all last season and never made plays like that. That’s definitely a good sign. Now we have to use that athleticism. We did a good job of using it in the first half. I would be lying if I didn’t say I got excited about some of those plays we made. Those were basketball plays.”

The season’s first week saw the Jays split a pair of games — a win over Oral Roberts, a loss to SMU — before they traveled to Lincoln to take on Nebraska. A brutal 85-57 loss could have indicated that the Jays’ optimism was unfounded, but Altman wasn’t having any of it. Down 21 points in the second half, he turned the game over to three of his freshmen: Buford, Mungin and Chestnut. The three had played sparingly in the first two games, but as Altman explained, “Those three guys earned that time. They did a much better job than some of our other guys did. I thought the freshmen were more aggressive. They made some mistakes defensively but they got out and ran and got after some people on defense.”

Altman was preaching that the players needed to practice well over more than just one or two days at a time before it would translate into success on the court, that they needed to show a consistent effort level. Buford bought in 100%. “I think we’re all getting more comfortable out there, but now, we just have to keep working hard in practice. We need everybody to keep doing that so that we can come together as a team.”

Over the first dozen or so games, though, the team failed to execute on that plan. They were 6-6 after 12 games; one night, they would play together and win, and the next, they would take a step backwards and lose. It was becoming clear, though, that the team’s fortunes would rise or fall on the backs of the freshmen, specifically Buford.

And on the morning of February 4, the Jays — winners of just 34 games the previous four seasons — sat at 11-9, with their confidence growing with each day. Buford was universally acknowledged as the key. In his first 20 games on the Hilltop, he accomplished the following:

- Averaged a team-leading 12.8 points per game. Meanwhile, his scoring average in his first 10 Missouri Valley Conference games was 14.4, and after he moved into the starting lineup in his 16th game, he averaged 18.0 points per game his first three starts

- Led Creighton in scoring in ten of 20 games. He scored 25 points in a 79-77 win over Southern Illinois on January 29, had 22 points in a Jan. 17 upset of two-time defending MVC champ Tulsa, had 19 points in a Dec. 6 loss to Nebraska and 22 points in a win at Wichita State on February 3.

- Shot 46% from the field and 38% from three-point range, leading the team in both categories. He also shot 68% from the free-throw line, but made 16 of 18 (89%) in the final eight minutes of games.

- Blocked 11 shots (tied for team lead), picked up 31 steals (second) and grabbed 68 rebounds (fourth).

Of course, unofficially, he also led the team in dunks and exciting plays.

When two-time defending champ Illinois State came to town on February 5, Buford was unstoppable, scoring 30 points in the game’s first 31 minutes as the Jays built a 10-point lead. The Redbirds rallied to go ahead, but Buford would score six points in the final 90 seconds to keep them in the game. And on the final possession, Altman drew up a play to get a game winning shot for his freshman star.

Trailing 73-72 with six seconds to play, the Bluejays got the ball to Buford on the baseline who drove hard past a screen, and pulled up to launch a seven-foot jumper. The shot hit the rim, then bounced away. Afterwards, Altman explained that “It was Rodney’s game to win or lose. He put us in that spot, and we weren’t going to give it to anyone else. He had a good look, jumped over the guy and shot it like he meant it. He just missed it.”

He scored 36 points that night on 12-21 shooting, including 4-7 from behind the arc. It was the first time in over three years — 93 games, to be exact — that a Jay had scored more than 30 points. He tied Benoit Benjamin’s school record for points in a game by a freshman, and at the time, the performance also tied him with Benjamin, Duan Cole, Chad Gallagher and Cyril Baptiste for 17th on Creighton’s single-game scoring chart.

“Rodney had a great game, but he can’t carry us by himself,” Altman said after the game. His lament was shared by his team. “The gym wasn’t big enough to hold Rodney tonight,” teammate Edward St. Fleur said. “It’s a shame we couldn’t win that one for him. He kept us in that game.”

Despite winning twice as many games as a year prior, they remained a team with one big offensive weapon surrounded by a collection of role players — and as his coach noted, he couldn’t carry them all by himself, no matter how well he played. And he’d played awfully well. He broke the freshman scoring record with 421 points, besting Benoit Benjamin’s previous high in 1982. He averaged 14.1 points a game, which was the 12th highest mark by a freshman in all of Division 1 that season. And he won the Missouri Valley Conference’s Freshman of the Year Award as well as the Newcomer of the Year Award, as well as earning a spot on the all-newcomers team, and he was picked by the news media to its All-Valley second team.

No Sophomore Slump

Before his second year, the respect for Buford’s talent was shown when he was picked for the preseason All-MVC Team, the only sophomore to be so honored. His high-flying style and impressive scoring totals, coupled with the preseason honors, meant he was no longer a newcomer flying under the radar. He would now draw the opponent’s best defender, and with no real second scoring option, their gameplan would center around stopping him. The single biggest question surrounding the Jays in Altman’s third season was whether Buford could accept the challenge.

Did he ever. Oh boy, did he ever. Buford had just two games where he failed to score in double figures — a nine point effort at Illinois State on December 29, and a seven point effort against Wichita State on February 20. In between, he scored 20 or more points a whopping 18 times — including a streak where he scored 20 or more in eight straight and 10 of 11 from January 27 until the end of the regular season. He upgraded his arsenal by improving his outside shooting, and also polished his moves to the basket and around the basket, making him hard to defend with a smaller player. Buford was becoming next to unstoppable offensively, and the rest of the MVC knew it.

Altman, however, was not happy with his progress on defense. After a 90-70 exhibition win in November, he held a 20-minute closed door meeting and tore the team apart — singling out his budding star. “When Rodney wants to guard somebody and wants to rebound, he can do those things because he is very talented,” Altman told the media afterward. “His mental toughness and his willingness to do that every possession of a ballgame are not there. I know Rodney gets tired of me screaming at him and yelling at him, and I get tired of screaming and yelling. But our job is to make him the best he can be. I’m really not sure Rodney is sure of his goals or how good he wants to be. But to his benefit, he’s put up with my nagging.”

It was a running theme. Altman would gush praise about his offensive skills, then express concern about his defense and rebounding. Especially on the Jays teams of his first two seasons, there was no one talented enough, quick enough or athletic enough to practice against, so he had to essentially practice against himself. He could only really improve his game during games, a fact Altman acknowledged and compared to the situation Mitch Richmond, another supremely talented player coaxed into greatness by Altman, faced at Kansas State. The light finally went on for Richmond and he became an All-American and NBA All-Star. He hoped the same would happen with Buford.

He tried to discourage the comparisons, though, until a moment of creative genius, of such supreme jaw-dropping skill, happened in a mid-February game against Indiana State.

The alley-oop pass was high, too high to catch, much less do something with, for most players. Yet Buford not only got to it, he got to it at its apex way above the rim, reached back and caught the errant pass behind his head with his right hand and, in one fluid motion, slammed it home while still in orbit, posterizing not one but two Sycamore defenders. Its seared in the memory of the 4,458 fans in attendance that night, and it remains the most spectacular dunk I have ever witnessed. Even Altman had to admit it was “pretty good,” adding “Mitch could do some dunking. But Mitch never did anything like that.”

By season’s end, he had averaged 19.6 points and 5.6 rebounds per game, and broken Paul Silas’ sophomore record for points scored with 589. He also became the first — and to date, only — player to eclipse 1,000 points by the end of his sophomore year. Bob Portman (1,195) and Paul Silas (1,124) own the highest CU scoring totals over the first two years of their careers, but both reached that mark as sophomores and juniors because freshmen weren’t eligible at the time. And for his efforts, he was named to the All-MVC First Team, the first Jay to be so honored since Duan Cole in 1991-92.

Realizing his Potential

As his junior year approached, the Jays were hoping that Buford could continue his historic pace offensively while improving his defense and rebounding. And with the departure of seniors Chuckie Johnson, Carteze Loudermilk and Edward St. Fleur, the onus was on freshmen Ryan Sears and Ben Walker to help out offensively.

His offense remained as explosive as ever, but he was finally showing drastic improvement in the two areas Altman so desperately wanted him to: defense and rebounding. And he was quick to give him credit. “A year ago he averaged maybe five rebounds a game, now he’s over seven,” Altman noted. “Defensively he hasn’t made nearly the mistakes he made a year ago. He’s scoring at about the same pace, but he’s making some shots for his teammates this year. He’s just taken steps in all three of those areas.”

Buford scored in double figures in all but four games, going for 20 or more points in 14 games and 30 or more twice. But that was old hat; he’d scored like that both of his first two seasons. What was new was the rest of his game. He had his first career double-double on November 29 when he scored 22 points with 10 rebounds, and he would go on to do it six more times that season — including a 28 point, 11 rebound night in a win over Drake; a 13 point, 13 rebound line in a win over Wichita State; and an 18 point, 14 rebound night in beating Northern Iowa.

The program was turning a corner, as it tried to firmly put the Rick Johnson years in the rear-view mirror — a fact that was evidenced on December 6 when they beat Nebraska for the first time in seven years. Buford, who scored 29 points, was locked in a duel with Husker guard Tyronn Lue, who scored 25. He was already showing his improved glass work, though, grabbing eight rebounds and making several mature plays with the basketball. The biggest came with the Jays leading 67-65 and just over 4 minutes remaining. Buford drove to the basket, but his dribble penetration was cut off by the Husker defense. In his first two seasons, he likely would have forced a shot. Instead, he pulled up and found a wide-open Matt West who connected on a three-pointer.

“Matt West hit a tremendously big shot,” Altman said in the postgame presser. “Everybody collapsed on Rodney when he drove. I really was afraid Rodney was going to force it there, but he did a very good job of recognizing, which is something he probably wouldn’t have done a year ago.”

His junior season was temporarily sidetracked on January 17, when Buford injured his ankle in a 61-58 loss to Bradley. He played just eight minutes in that game, but when he returned three nights later against SMS, his teammates had seemingly grown overnight into the kind of offensive sidekicks he’d longed to play with. Doug Swenson had a (then) career high 23 points, Ben Walker had his highest point total of his young career with 20, and Ryan Sears added 16 points, eight assists and six steals. Buford had 20 points, seven rebounds and seven steals in 35 minutes. Over the next couple of weeks, the Jays finally began playing the tenacious, up-tempo style they’d become known for under Altman, as he felt he finally had the horses to do it. And they began running teams out of the gym in the process, rattling off a nine-game winning streak starting with the January 21 win over SMS.

In that nine-game winning streak, Buford grabbed the MVC Player of the Week award all three weeks by averaging 19.8 points on 49.3% shooting, 8.7 rebounds, 3 steals and 2.7 assists a game. Over a three-week span, he finally put together a stretch of games that lived up to the potential Dana Altman always believed he possessed, as he continued scoring in huge numbers but added defense and tenacious rebounding to his arsenal.

And in winning nine straight, they had won more games in three weeks than they had in any of Rick Johnson’s three seasons, and had positioned themselves for a return to the postseason — which they would get when they were invited to the NIT.

The hard work by the Jays, including Buford, to bring the program back into postseason consideration was enough to nearly bring Altman to tears at a press conference following their elimination from the MVC Tournament — a rare glimpse into that side of him. “I wish it could have ended better. We’ve got great kids. Sometimes I get mad at them when they don’t do what we want. But I really like our kids. I just didn’t get them tough enough down the stretch. I didn’t get them prepared. But we did a lot of good things this year. I don’t want that to get lost. If they (NIT) want a team, we’d love to play.”

A 80-68 loss to Marquette did nothing to dim their turnaround season, in which they went 18-10 and 12-6 in the MVC, tied for second place.

Buford finished the season as the first Bluejay to lead the league in scoring (18.9 points per game) since their return to the MVC in 1977, but he also finished as the sixth-best rebounder in the league as he pulled in an average of 7.4 caroms a game. He was one of just 20 players in the 91-year history of the MVC to score 1,500 points in his first three seasons, and was just 571 points shy of Bob Harstad’s school-best 2,110. His improved rebounding had also brought him to the periphery of the school’s all-time top ten list in that category. And he was named to the first-team All-MVC squad for the second straight year, earning the second most votes and finishing as the runner-up in Player of the Year balloting to Rico Hill of Illinois State.

Capping Off a Stellar Career

As his senior year came, expectations for both Buford and Creighton were high. They embarked on a tour of Europe in August, where they went 4-1, and when the preseason predictions came out, the Jays were picked to win the league — and Buford was a unanimous choice for preseason player of the year.

In their first big test of the season, a road game in Iowa City against an Iowa team that had played in five of the previous seven NCAA Tournaments, the Jays got a hard-fought 75-73 win as Buford piled up his first double-double of the season. He scored 24 points, with 11 rebounds and 7 assists in a monster game that saw him score buckets on five consecutive possessions in the second half as the Jays moved to 3-0 for the first time to open a season since 1980-81.

They were 6-2 when former coach Eddie Sutton brought his 18th ranked Oklahoma State Cowboys to the Civic Auditorium on December 20, but for the first time since his freshman year, Buford didn’t start — the result of disciplinary action after he showed up four minutes late to practice. He came into the game with 14:48 left in the first half and Creighton trailing 11-10, then went on to score a team-high 20 points in 27 minutes as the Jays pulled off the 66-60 upset.

Ten days later, sitting at 8-2, they took on Bradley in front of a robust 3,083 fans at the Civic. Buford had perhaps his greatest individual performance of his career, as he hung 40 points on them. He was a ridiculous 13-17 from the field, 8-8 from the free throw line, 6-8 from behind the arc — and added 8 rebounds. To no one’s surprise, it was the latter that drew praise from his coach. “He was really focused tonight, not only on the offensive end but defensively. He tried to guard, had those knees bent and really put in an effort.” His 13 field goals nearly eclipsed the team total for Bradley, who made just 16 in a 65-44 pasting.

In late January, they went into first-place Evansville and outscored the highest scoring team in the league, 90-80, in a wild game that saw Buford score 28 points while making 13 of 16 shots and grabbing 9 rebounds. Later that week, he scored 22 with 9 rebounds in a win over second-place Illinois State. He once again earned MVC Player of the Year honors for his efforts.

He passed Chad Gallagher and moved into second place on the all-time scoring list on February 14, highlighted by a steal and a fastbreak tomahawk dunk that ESPN couldn’t get enough of — but when a potential game winning shot clanged off the rim, the Jays lost to Illinois State 79-77. Buford was left to ponder his fate as his reputation in the media and among fans was becoming cemented as the player who could score at will but who could never quite do enough to please everyone or to win championships. He was going to pass Bob Harstad and be the leading scorer in school history, yet no one would ever say Buford was the better player. He was running out of games to change that fate.

Prior to the MVC Tournament, Buford was named to his third consecutive All-MVC First Team, though he finished second in Player of the Year balloting for the second consecutive year, this time to Evansville’s Marcus Wilson. Altman summed up his importance. “Four years ago when Rodney got here, we were awful. We were looking for somebody to hitch our program up to and go. He turned out to be that guy.”

But as the Jays advanced through the weekend to the MVC Title game on Monday night, Buford turned in two of his worst performances of the year — first, a 4-point stinker against Illinois State in the quarters, and then a 16 point game with three horrible turnovers in the semifinals. His first half of the title game wasn’t going much better, until Ben Walker lit into him at halftime.

Buford recalled the conversation this way. “He said, ‘You’re not playing like you should, you’re not rebounding and on the offensive end you’ve got to take over.’ That’s what I thought I had to do. I wanted to be the difference-maker.”

Altman was amazed. “Ben should take over the coaching duties. He’s the one who got him to play. I’ve screamed at him all year and it never did any good. But Ben tells him to rebound and he goes and rebounds.”

He had 21 points and 13 rebounds, and scored six consecutive buckets in a decisive late-second half stretch that the Omaha World-Herald described thusly:

The 6-foot-5 forward from Milwaukee went into the lane and made a tough one-handed shot, then followed with a 3-pointer to make it 53- 48.

Marcus Wilson, the MVC player of the year, fired back with another 3- pointer as the pace picked up. But Buford stung the Purple Aces with a basket inside before stealing a pass and going in for a two-handed dunk.

Creighton, now ahead 57-51 with 7:59 remaining, knew what to do with the lead. The Bluejays made 7 of 8 free throws and got a dunk from Doug Swenson over the next five minutes as the advantage grew to 66-52.

They would close out a 70-61 win, and earn the automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament — their first of the Altman Era.

In the NCAA Tournament, they were shipped to Orlando, where they met the Louisville Cardinals. The entire team, new to this thing, seemed to have stage fright; they were missing open shots, leaving shooters open, not making plays they normally made. They were behind by 13. And then, Rodney dove for a ball, tumbling out of bounds and risking the horrible fate of a floor burn to try and save a ball.

“Rodney’s not the kind of guy who will throw his body on the floor if he can help it. When we saw that, that fired us up,” Walker said afterward. The determined play from Buford snapped the team out of their stage fright, and then Altman turned the dial up on their 3-2 zone, and then…

Somehow, Buford came up with a steal around midcourt and raced to the other end for one of his patented dunks. Walker hit a 3- pointer. Methodically, the Jays first climbed back into the game, then forced a tie, then got a lead, and suddenly the Orlando Arena was a madhouse. Anyone not wearing Cardinal red was a Bluejay fan. And with 2:13 left, it was Buford, whose dive had fired the team up, who hit the dagger, a deep three-pointer that gave them a 52-49 lead they would not relinquish.

Altman was absolutely giddy afterwards. As Tom Shatel described it,

“FIRST LEGITIMATE DIVE!” yelled Creighton Coach Dana Altman, as he and Buford walked off the floor at the Orlando Arena after talking to CBS. Altman had his arms around Buford’s neck and wore a smile as big as Disney World. He was a father hugging his son after his first hit, his first time on a bike without falling or his first “A” on the report card.

No one could remember just when it happened – they say it was the first half – or if Buford even got his hands on the ball. No matter. What was stop-the-presses news was that Buford had gotten his Bluejay feathers dirty.

Altman scores the most points for those little hustle plays. For four years, Altman has been trying to get Buford to hustle, to play hard. To dive. Just once. He would trade all those points and dunks and highlights by Buford for one dive. Finally, so did Buford.

Two days later, Buford’s career would end with a 75-63 loss to Maryland in the second round, but not before he surpassed Bob Harstad as the leading scorer in Creighton history. He scored 20 or more points an astounding 57 times. Yes, 57. His career average of 17.9 points is fifth highest, his 195 steals are third most in Jays history, and his 212 three-pointers are also third most. But perhaps most satisfying for Dana Altman? The guy who didn’t want to rebound ended up with 716 of them, good for sixth best in program history.

As for Buford, the player who on the night he passed Chad Gallagher on the scoring list wondered if his fate would be that of a fantastic offensive player who couldn’t win championships, he’d carried the team to victory both in the MVC and the NCAA Tournaments. Harstad is still considered by most to be the best player in school history despite Buford passing him on the scoring list, but for the kid who signed on the last day of the spring signing period in 1995 after no one else wanted him, scoring 2,116 points and helping put a once-proud program that had fallen on hard times back on the map is a pretty good fate. Pretty good indeed.

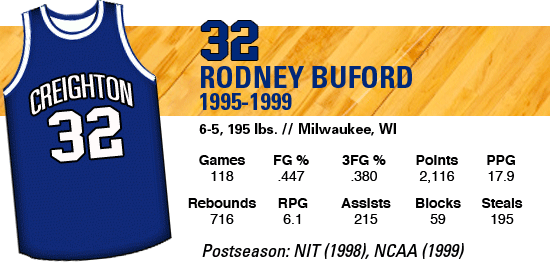

Career Stats:

Season FG Pct. Pts Avg. Reb RPG Assists Blocks Steals

1995-96 .462 421 14.5 122 4.2 41 24 49

1996-97 .439 589 19.6 168 5.6 48 18 44

1997-98 .424 530 18.9 204 7.3 58 9 43

1998-99 .469 576 18.6 222 7.2 68 8 59

Totals .447 2,116 17.9 716 6.1 215 59 195