ED. NOTE: White and Blue Review’s ongoing series “What’s in a Number?” continues with a look at the best player to wear #44 for the Jays, Rick Apke. To read up on how we arrived at our choice, check out the introduction of the series. Or you can read about the players you might have missed by checking out the entire list.

I know what you’re thinking. What about Anthony Tolliver? The big man who anchored two NCAA Tournament teams in the middle part of this decade, who grew from a project player into an NBA talent? Certainly he was a fine player for the Jays. But Apke had set the bar so high, even the A-Train’s stellar final two seasons were not enough to eclipse it.

The decade of the 1970s was a good one for Creighton basketball. They went to three NCAA Tournaments and one NIT, winning two games in the 1973 NCAA Tourney and coming *this* close to upending fourth ranked DePaul in the 1978 tourney. Two of those NCAA teams, as well as the NIT squad, were led by Rick Apke.

Of course, the decade of the 2000s was a good one too — the Jays went to five NCAA Tournaments and four NITs. Anthony Tolliver was a leader on two of those teams, as well as one of the NIT teams.

Both scored over 1,000 points in their careers: Apke with 1,682 to Tolliver’s 1,004. Both grabbed a ton of rebounds: Apke is seventh in school history with 709, while Tolliver had 603. Tolliver barely played as a freshman and struggled so massively for most of his sophomore year that he almost left the team before having 2+ great seasons; Apke was stellar for four seasons, and hit the most famous shot in school history. Again, I know what you’re thinking, What about Terrell Taylor? His shot was big. Apke’s shot was bigger.

Creighton basketball existed before 2002, believe it or not. In fact, you could argue its true golden era was the 1970s, and the best player of that golden decade — as voted by the fans in a 1980 Omaha World-Herald poll — was Rick Apke by a landslide. The 1978 team was so good that three of its starters, as well as its head coach, are members of the Creighton Sports Hall of Fame (Kevin McKenna, John C. Johnson and Rick Apke, as well as coach Tom Apke). So while Tolliver was great, he did not eclipse the accomplishments of Apke.

***

When Eddie Sutton departed in the spring of 1974 following an NCAA Tournament run, his longtime assistant — and former Creighton player — Tom Apke took over as head coach. During his first spring of recruiting, he was engaged in a fierce battle for an outstanding 6’7″ forward out of Cincinnati that Big Ten power Michigan wanted badly. The Wolverines had been after him for a while; Apke and Creighton came in late in the process.

Coach Apke recalled in 1989, “When the recruiting got hot and heavy, I said he ought to get an unlisted telephone number and give it out only to family members.” Why would that make a difference, you ask?

The player was Rick Apke, younger brother of the Coach. And the younger Apke wound up picking Creighton over Michigan, which probably wasn’t terribly surprising; his mother knew the coach pretty well, after all, and was comfortable sending her son to play for him. So it was done: Apke would go play for Apke, the younger brother playing for his older brother.

Upon arriving at Creighton, he found himself in a supporting role in his freshman season as the Jays plotted a return trip to the NCAA Tournament. The Jays lost in a whopping three in-season tournaments that season. In their own Creighton Cage Classic, they beat Santa Clara but lost to UTEP in the title game 69-63; in the Indiana Hoosier Classic, they lost to Indiana 71-53 in the opener before winning the third place game against SMU, 73-59; and in the Far West Classic, they lost to both Oregon and Wake Forest, with a win over Boston College sandwiched in between. Despite those losses, they would rally to beat Drake in Des Moines, 71-70, on January 2…and they would not lose again until early March! A 14-game winning streak saw Doug Brookins emerge as the team leader, he averaged nearly 20 points and 10 rebounds over the two-month stretch. During that stretch, Apke provided solid minutes in support of the starting five, and he averaged 6.4 points and 4.2 rebounds for the season.

The team earned a matchup with #4 Maryland in the NCAA Tournament, and were sent to Lubbock, Texas. Apke cut his postseason teeth in that battle, scoring 4 points and securing 2 rebounds in limited minutes that would prepare his nerves for big games later in his career.

***

As a sophomore, standouts Charles Butler and Doug Brookins had departed, and the Jays looked to junior Daryl Heeke to shoulder some of the load. Instead, it was Rick Apke who grabbed the mantle of team leader, emerging as a dominant force both on offense and defense. He led the team in scoring (16.4 points per game), rebounds (7.7), field goal percentage (54.4%), and free throw percentage (79.4%), was named the team’s Most Valuable Player, and was an Honorable Mention AP All-American. The team finished with just one fewer win the year before, going 19-7, but in the days before multiple tournaments they were left out of postseason play.

The Jays would return to the postseason the next year, as they piled up a 21-7 record and an NIT bid. It would be their final season as an independent after 29 years of flying solo, and they made the most of it, scheduling the last of their “Travelin’ Jays” slates with games against #20 Auburn, #14 Louisville, and #19 Marquette — as well as games with perennial powers Tulsa and DePaul. Rick Apke improved his offensive output, once again leading the team in scoring (19.8 points per game) and field goal percentage (57.8%) while finishing second in rebounding with 6.2. Once again, he was named the team’s Most Valuable Player, and once again, he was named an Honorable Mention AP All-American.

In the NIT, the Jays were matched up with future MVC opponent Illinois State in Omaha. After trailing early, John C. Johnson scored 10 straight points in an amazing second half stretch that eliminated a 51-44 deficit and brought them within one. Apke fouled out on the next possession, the Redbirds sank both free throws, and they never looked back.

After three seasons, he was already among the all-time greats on the Hilltop. He’d twice been named an Honorable Mention AP All-American, joining the great Paul Silas as the only Jays to do so more than once. He’d twice been named team MVP. He’d played in two postseasons. He was already a member of the prestigious 1,000 Point Club, and his 555 points as a junior were the ninth most in a single season in Jays history at the time.

Amazingly, he had saved his best for last. Oh boy, had he ever.

***

The 1977-78 season saw the Jays welcome Kevin McKenna to a solid core including John C. Johnson, Randy Eccker and Rick Apke — and it saw them rejoin the MVC after a 29-year absence. And they got off to a shaky start, winning 9 of their first 14 games but going just 4-3 in league play before a trip to Terre Haute in late January to face Larry Bird and the Indiana State Sycamores.

Bird was a junior, a first-team All-American and the nation’s leading scorer. The next year he would lead Indiana State within a game of an unbeaten season, with the only loss coming to Michigan State and Magic Johnson in the NCAA Championship game. In 1977-78, they were just as good, albeit a year younger and slightly less seasoned.

On the night of January 28, bad weather delayed the Jays from arriving on time. “The good news is the Bluejays have finally arrived in Terre Haute,” Apke announced in a phone call to the team’s beat writer at the World-Herald in the middle of the night. “The bad news is that Indiana State also made it.”

The Sycamores had been 13-0 before leaving on a three-game road trip where they dropped all three, and the fear among Bluejay coaches and fans was that Indiana State would come out angry and blow them out. Early on, those fears looked prescient when the Jays fell behind by 14 in front of a frenzied crowd. The Sycamores had won an amazing 30 straight games at home, and had no intention of seeing their streak snapped at the hands of a conference newcomer in their first trip to the arena.

Things looked even worse when both McKenna and Johnson got in early foul trouble. Luckily, the scoreboard wasn’t working. The always quotable Coach Apke said afterwards, “We just didn’t tell our kids how far they were behind and they didn’t know the difference. Then when we got the lead back and we were running the stall, the timeclock worked again and helped us. Think I should give them back the fuse I grabbed?”

An amazing second-half rally, fueled mostly by Apke with the Jays other stars in foul trouble, put them ahead, and then the Jays held on to win 72-64. Bird scored 32 that night, and Apke 21 on 9-17 shooting while grabbing 15 rebounds and dishing out 2 assists. The sports section of the World-Herald the next day, as it did every Sunday, was titled “Blue Streak Sports” — a title that may not have made much sense for day-after Husker football recaps, but was apropos on that day. The headline?

“Bluejays Give Indiana State a Birdbath”

Great stuff.

***

The rematch in Omaha two weeks later had a huge buildup, as the Jays had used the previous win to jumpstart their season — going 5-2 over their next seven games, with the only losses being a triple-overtime heartbreaker to #13 DePaul at the Civic, and a loss to #3 Marquette in Milwaukee. The game would likely put the winner in position to win the regular season title.

Unfortunately for Indiana State, most of their team — including Larry Bird — came down with the stomach flu the day before the game. Playing in a weakened condition, Bird scored a career-low 11 points as the Jays destroyed the visitors, 89-57.

***

The Jays went on to win two of their final three games, earning the regular season crown with a 12-4 record in the league. Back then, the champion got a bye into the the title game, while the other eight teams played off for the right to travel to the champions home gym to play for the title. So while everybody else played, the Jays sat…for eight long days. With an offense predicated on precision passing and cutting, the long layoff concerned coaches who feared the team would be rusty.

Meanwhile, Indiana State beat West Texas State, Bradley and New Mexico State, the latter in two overtimes, to punch their ticket to Omaha. The grueling battle left Bird’s notoriously sore back in bad shape; he spent the entire day before the game — and the hours leading up to the game — in an Omaha hospital getting treatment for back spasms.

“Not a lot of people know that,” Rick Apke told the World-Herald in 2003. “There was some question whether he’d play. When we came out for warmups, we saw him going through some layup drills, but you could tell he was being very careful. But he wound up playing, and playing very well.”

NBC picked up the game as part of their weekend college basketball package, and sent it to affiliates in MVC cities; most of the country got the Michigan-UCLA tilt, but they cut in at the end and most of the nation saw the final moments. It was the first nationally-televised Creighton game from the Civic.

As for Bird’s bad back? Like all the great ones, he had the ability to flip a switch come game time and dominate despite obstacles, and he certainly didn’t play like he had a bad back on this day. After missing his first shot, he didn’t miss again the rest of the game, making his last 11 shots from the field and all seven of his free throws. He finished with 29 points, and scored all but two of Indiana State’s 20 second-half points, while making 11-12 field goals, 6-7 free throws, grabbing six rebounds and three steals, dishing out three assists AND holding the Jays’ David Wesely to just six points, well below his season average. It was truly a virtuoso performance. He lit the gym on fire with his shooting, and the packed house was forced to bottle their noise and energy as the Sycamores built a double-digit lead.

His final bucket of the day, with 6:20 to play, gave Indiana State a 52-44 lead. Coach Apke called in a press they called “Monster.” It forced four consecutive turnovers, including two straight ten-second calls, as the noise in the Civic ratcheted up more and more.

Meanwhile, Kevin Kuehl hit two shots and Kevin McKenna one off the first three of those turnovers, and suddenly the deficit was just two. The fourth turnover, a long pass that sailed wild over Bird’s head and out of bounds, led to a 20-foot jumper from Rick Apke that tied the game at 52 with 4:30 to play.

Coach Apke, watching Bird light the gym on fire with his shooting, decided his best chance at victory was to prevent Bird from shooting — and the best way to do that was to not give them the ball back. And so the Jays dropped into their “Five-Ball” offense on the next possession. With no shot clock and no three point line in 1978, a lot of teams had a delay offense in their arsenal, Creighton among them. Dana Altman would have loved it.

“We were disciplined and trained to only accept a layup when we were in the offense,” Rick Apke told the World-Herald in 2003. “But since they had played us twice before and scouted us, Indiana State played off of us and did a good job of not letting us get any backdoor cuts for layups. Frankly, that was one of the rare times in that offense where we didn’t get fouled or get a layup.”

And so for over four minutes, the Jays and Sycamores played a game of cat and mouse. They toyed with each other, like boxers in a heavyweight fight circling each other looking for an angle. Pass after pass went inside and out, side to side, four exhilarating minutes of the Jays playing keep away while simultaneously hoping for a defensive mistake allowing them an easy basket. The crowd noise inside the Civic reached unfathomable levels. Finally, with 23 seconds left, Coach Apke called timeout.

The play call? Something called “Sarah”, named after a fan who happened to be watching practice the day Coach Apke had unveiled it three years earlier. The idea was for Randy Eccker to dribble penetrate into the lane and get the ball to any of three options. Trouble was, the Sycamores came out in a trap, and their harassing on-ball defense refused to allow the play to develop. Time was ticking down. Somehow, he fought through the trap, dribbling wildly, and then he saw Rick Apke out of the corner of his eye.

Apke was closely guarded at the top of the key. “By the time he got me the ball, there was something like seven seconds left,” Apke told reporters after the game, adding that if he had more time, he’d have looked for better options closer to the hoop. But time was not his ally. “I knew I had to do something with it, so I figured I might as well shoot it.”

And so he did. Apke threw up a fallaway jumper from 21-feet out; as it hung in the air the crowd went deathly silent. Ask anyone who was there, and they’ll tell you time seemed to stand still. As it swished through the net, the silence remained for a split second — the crowd in disbelief — before erupting in a noise unlike any the old barn had heard before or since.

As Eccker recalled in 1989, “In a lot of years in athletics, as a player and as a coach, that may have been the loudest crowd I’ve ever heard.”

Suddenly the Jays had a 54-52 lead with three seconds to play. Apke then batted down a desperation baseball-pass on the inbounds play, and the crowd stormed the court, lifting both he and Eccker in the air. “For 34 minutes, that really wasn’t a great game,” Eccker said in a 2003 World-Herald interview. “But those last six minutes made it a classic.”

Apke finished with 13 points and 6 rebounds. Not that it matters. He made The Shot.

***

Creighton’s third win over Larry Bird’s Sycamores earned them a trip to the NCAA Tournament, where they were “rewarded” with a rematch against DePaul. Their first game was a triple-overtime thriller in Omaha, won by the Blue Demons 85-82.

“We felt we had a score to settle with DePaul in that game,” Eccker recalled in a 2005 World-Herald article. “We knew how to play them and we felt, based on what happened in the first game, that we were every bit as good as them.” Strong words, perhaps, considering DePaul’s lofty ranking — they had risen to #4 in the country by the time of the tourney.

The game immediately preceding the Jays/Blue Demons matchup went four overtimes — FOUR! — as Missouri and Utah went at each other. Meanwhile, the Jays and Blue Demons paced in their locker rooms, their game delayed more than an hour. When it finally tipped, the Jays burst out to a 21-point lead in the first half, their defensive plan working like a masterpiece: pack the defense in around All-American center Dave Corzine, and force them to make outside shots.

DePaul guard Randy Ramsey was the beneficiary of that defensive strategy, and he had open look after open look. And he missed almost all of them.

The Jays had shot over 70% from the field in the first half while DePaul shot 35%; in the second half, those totals reversed. The open looks Ramsey had missed in the opening stanza were now going in. Corzine, who had lit up the Jays for 31 points in the team’s first matchup, was held down but the gamble to make Ramsey and others beat them — a gamble that looked genius in the first half — suddenly looked like a sucker’s bet.

After tying the game at 78 with under a minute to play, DePaul made two free throws to take the lead. Then they forced a jump ball on the next possession; the Jays won the tip, and Rick Apke wound up with the ball 35 feet from the basket as the clock ticked towards zero. He threw up a prayer of a shot that was wide. McKenna snared it out of midair and dunked it.

A split second after the horn had sounded, unfortunately.

“That was probably one of the best dunks that I had, and it didn’t count,” McKenna recalled in a 2005 World-Herald interview.

The loss was extremely frustrating on a number of levels. With the NCAA Tournament being just 32 teams back then, a win would have meant a Sweet 16 berth and a matchup with Louisville — a team the Jays had played in Louisville the year before and taken to double-overtime before losing. Awaiting if they’d handled the Cardinals? A Notre Dame team they had also proven they could compete with, a Final Four berth on the line.

As Eccker noted in 2003, “DePaul kind of used that win over us to become a nationally elite team. We knew we were so close to possibly doing the same.”

***

For his career, Apke finished with 1,682 points, which was second-best all-time when he graduated and ranks seventh currently. He led the team in scoring each of his final three seasons, was named team MVP each of those seasons, and was named an Honorable Mention AP All-American each of those three years — and along with Paul Silas, is one of just two players in Creighton history to be a three-time All-American.

His 673 field goals made is sixth-best all-time, his .535 field goal percentage is seventh best, his 709 rebounds are seventh most, and he is one of just a handful of players with two 500-point seasons. He’s also the author of the greatest shot in Creighton history.

It isn’t that Anthony Tolliver wasn’t great. Its merely that Apke set the bar so high, even a stellar career by the A-Train couldn’t eclipse it. Rick Apke was then, and remains, the greatest #44 in Creighton history.

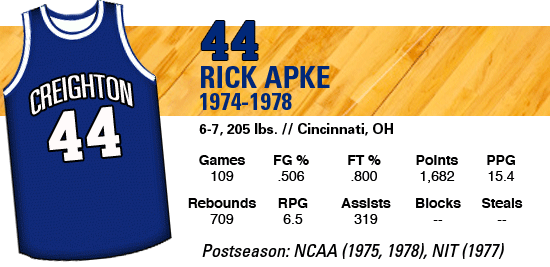

Career Stats:

Season FG Pct. Pts Avg. Reb RPG Assists Blocks Steals

1974-75 .511 175 6.4 114 4.2 33 - -

1975-76 .544 439 16.8 202 7.7 89 - -

1976-77 .578 555 19.8 175 6.2 80 - -

1977-78 .496 513 18.3 218 7.8 117

Totals .506 1,682 15.4 709 6.5 319 -- --