Terrence Rencher still remembers the one and only time his father took him to see a game at Madison Square Garden. These were the pre-Patrick Ewing days so the Knicks still weren’t any good, he says, but who won the game didn’t make the cut of his fondest memories from that day. The first-year Creighton assistant coach remembers fans being allowed to come down late in the game and tap players on the shoulder for autographs. He remembers walking with his father and younger brother to the train station and seeing back-up center Marvin Webster ordering a snow cone from a vendor on the street outside the arena. He can even tell you where the three of them went to eat after the game.

Terrence Rencher still remembers the one and only time his father took him to see a game at Madison Square Garden. These were the pre-Patrick Ewing days so the Knicks still weren’t any good, he says, but who won the game didn’t make the cut of his fondest memories from that day. The first-year Creighton assistant coach remembers fans being allowed to come down late in the game and tap players on the shoulder for autographs. He remembers walking with his father and younger brother to the train station and seeing back-up center Marvin Webster ordering a snow cone from a vendor on the street outside the arena. He can even tell you where the three of them went to eat after the game.

“We went to one game and we went to one restaurant,” Rencher said. “My mother went out of town to my cousin’s wedding and my father wasn’t into all of that, so we stayed here. He took us to the game and then to Beefsteak Charlie’s. It was the one time we went out to dinner as a family back then.”

As far back as he can remember, Rencher, now 47 years old, always had a basketball in his hand growing up in The Bronx, New York. The neighborhood kids used poke fun at him for it, but he didn’t care. It didn’t matter what the circumstances were, he was always looking for a place to play or a game to watch. Basketball was in his blood.

“That was just life to me,” he says. “Playing basketball every day for hours and hours. Playing anywhere that you can — glass on the court, puddles, syringes, whatever the case may be.

Traveling to other neighborhoods and getting chased out of parks … all we wanted to do was challenge ourselves against anybody in the city all the time.

“It was just a way of life. My dad was a basketball player and a big fan, my older brother was a player and a big fan, so I was always around it. I was always in the gym, I was always sitting in front of a TV. It’s just what I knew. Every day was like that. It was just an obsession. It was just something I loved to do. I don’t remember my life without it.”

It wasn’t long before he garnered the reputation as the best player in his neighborhood. Once his dad picked up on that, it was time for a shove.

“I think I was like 10 or 11 years old and he was like, ‘listen, this ain’t enough for you around here,'” Rencher recalled his father telling him. “‘You need to go and start playing against some kids from Brooklyn and Queens, you need to go out and play. You’re not going to get any better by doing this.’ He was the one who pushed me to go expand and challenge myself against other kids in the city.”

The rest of Rencher’s New York City story is history. He attended St. Raymond High School for Boys in The Bronx and was named city MVP and Mr. Basketball in the state as a senior in 1991. He had four dream schools that he wanted to play for after high school — St. John’s, Syracuse, Virginia, and Maryland — but for one reason or another they each either slow-played him or didn’t recruit him at all.

Then shortly before his senior season he saw the Texas Longhorns playing on TV and fell in love with the style of play and the freedom it gave the guards to flourish (a lot like a certain point guard currently enrolled at Creighton), and it stuck with him. He scheduled his first official visit to Austin in November and shut down his recruitment when he got back home. His parents were a little apprehensive about the destination and the distance from home, but it wasn’t enough to override the pride they felt as he was about to become the first member of his family to attend college.

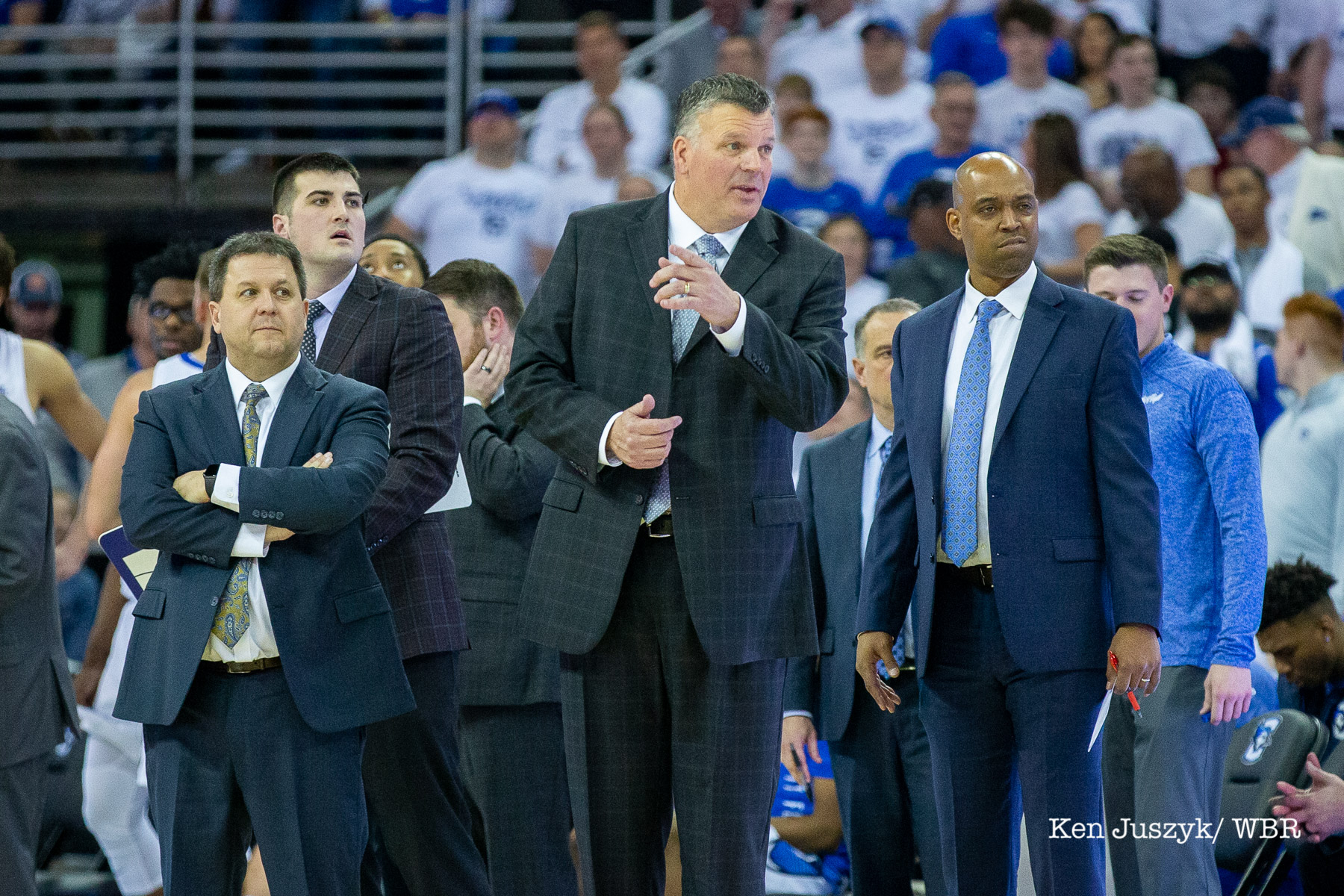

He started at shooting guard all four years in burnt orange and finished his career as the school all-time leader in points with 2,306, steals with 255, and field goals with 326. He helped the Longhorns win three Southwest Conference regular season titles before getting selected 32nd overall in the 1995 NBA Draft by the Washington Bullets. Rencher spent two seasons in the NBA, then played overseas from 1997 to 2007 before going back to Texas to get his degree. Then came coaching stops at Saint Louis, Texas State, Tulsa, Sam Houston State, New Mexico, and San Diego before Creighton came calling shortly before Thanksgiving.

“My first thought was that it’s just a good opportunity in terms of being a part of this program,” Rencher said. “Then obviously when you peel back the next couple layers of it I realized that I finally get to be a part of the Big East.”

As unlikely of a destination as Austin, Texas was for an 18-year-old from The Bronx, Omaha, Nebraska would have topped it in that regard once upon a time. But despite the geographical contradiction, Creighton offers Rencher an opportunity to not only fill a competitive void in his coaching career by competing in a high major conference, but it also affords him the chance to retrace his steps and revisit some fond memories. Like the one he made back in the early-80’s when it was just a Rencher boys night at The World’s Most Famous Arena.

That one game, that one restaurant, that one special memory.

He cherishes that night even more now because exactly 51 days after Creighton brought him on board his father passed away.

Paul Rencher, Sr. wasn’t in what you would consider great health at the time of his death. He had been in a rehabilitation facility since October recovering from liver cancer which produced a tumor that pressed up against his spine and inhibited his ability to walk. Yet despite all of that, his passing on January 16 — four days shy of his 72nd birthday — still came as a shock. Rencher had just spoken to his mom that morning and she told him she would call him later that night to update him on how his father was doing, so when she called again soon after as he and the Bluejays were about to huddle up on the court after a film session at the Championship Center, something didn’t feel right.

He peeled off to the back staircase that leads up to the coaches’ offices and began to break down as his mother told him the news.

“We had just talked about him being here,” Rencher said. “Getting out of there and getting strong again so at least by the time we got to the conference tournament he could come check us out. It was surreal. He was gone.

“And for me, it was painful, but the real pain was hearing the pain in my mom’s voice. On top of it that was the part that was really hard for me to deal with because you don’t like to see your people in pain. But it was just like, ‘man, really? I’m not going to talk to him anymore. It’s over.’ That was hard, and it’s still kind of hard to deal with. I think about him all the time.”

He even caught himself late in Creighton’s Big East title-clinching win over Seton Hall on the last day of the regular season wondering what his father would think if he could be in the arena with him.

“It choked me up on Saturday because my father would have loved that,” Rencher said. “Ty-Shon made that layup to go up seven, they called a timeout, and the place went crazy. That was the first moment where I kind of got outside of myself. I started getting goosebumps and my heart started beating fast. It was like, ‘oh shit, we might be Big East champions here in a little bit.’ Then we kept playing well and as the time was winding down I was just sitting there — I felt good, I’m not going to say I felt sad, but I wish he could have seen that. I wish he could have seen the scene, or just the final score, or just witness a little bit of it. He would have been ecstatic.”

Although he can’t share moments like that in person with his father anymore, Rencher knows that the man who guided the player he was once upon a time and the father that he himself is now will be there in spirit when the top-seeded Jays tips off at noon on Wednesday at Madison Square Garden. 35 years later, the son returns the favor by taking the father with him to the arena located a half an hour from where they built that bond through basketball on the blacktops of the Bronx.

“He’ll definitely be in the building with me. In THAT building for sure … there’s no question.”